Symphonies

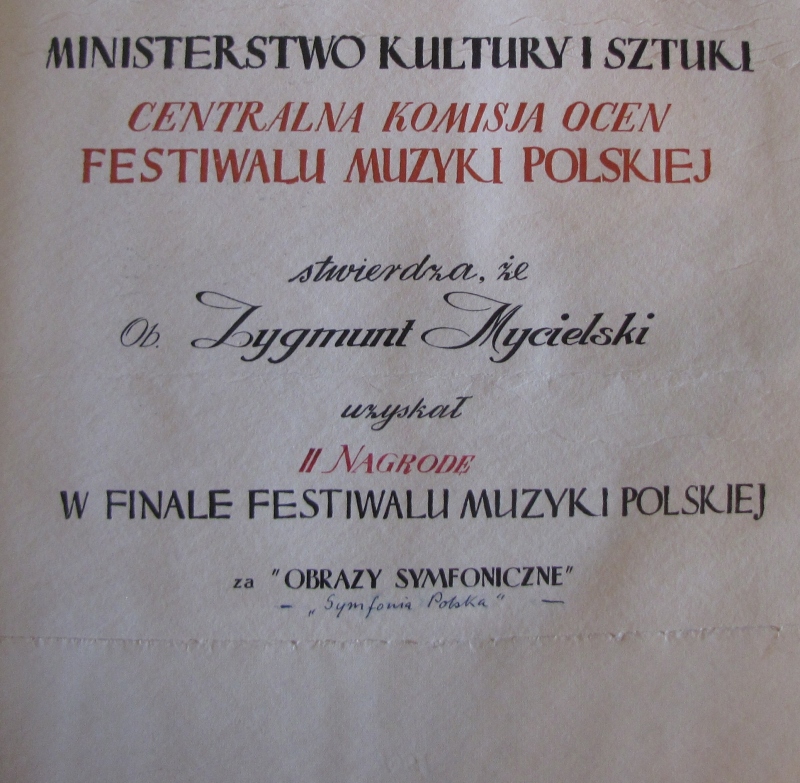

Zygmunt Mycielski’s orchestral oeuvre is made up of six symphonies (“Polish” Symphony, 1950–1951; Symphony No. 2, 1957–1961; Symphony No. 3 “Sinfonia breve”, 1961–1967; Symphony No. 4, 1968–1973; Symphony No. 5, 1974–1977; Symphony No. 6 or Last Symphony, 1985–1986) as well as some less elaborate works (symphonic “elegy” Lamento di Tristano, 1938, rev. 1947; Five Symphonic Sketches, 1945; Silesian Overture, 1948; 6 Songs for orchestra, 1978; Variations for small string orchestra, 1979–1980; Fantasia for orchestra, 1981).

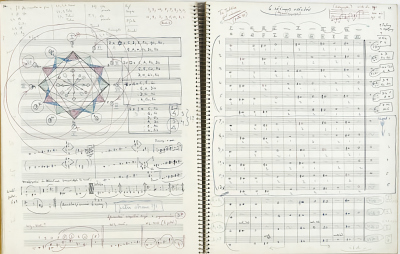

This material is complemented by interesting drafts for Mathematical Variations (ca 1957) and a composition entitled Meletemata (1969), which are part of the Zygmunt Mycielski Archive at the Manuscript Department of the National Library. Although the symphonies, Silesian Overture and Lamento di Tristano were published by Polskie Wydawnictwo Muzyczne - PWM Edition, and the premieres were well received by the critics (though there was a lack of understanding from the moment Mycielski began to compose on the basis of his table system), the works remain essentially unknown.

The few archive recordings circulate “in samizdat” and Mycielski is known in musical circles primarily as a philosopher of music, author of essays included in the collection Postludia and a number of articles collected in Ucieczki z pięciolinii, Notatki o muzyce i muzykach, Szkice i wspomnienia and Znaki zapytania.

However, even during his lifetime he witnessed an almost total indifference on the part of his fellow musicians towards his music, finding support in Andrzej Panufnik and a circle of friends met during his years of study with Paul Dukas and Nadia Boulanger at the École Normale de Musique. In addition, we need to bear in mind the external reasons behind the absence of Mycielski’s music from programmes of concerts and festivals. First of all, he came from the nobility, so when he entered the music scene as a mature artist, his background did not make it easy for him to function in the reality of communist Poland. Secondly, the ideals of truth, goodness and beauty, respect for his homeland, centuries-old traditions and customs – ideals instilled in him at the Wiśniowa manor – shaped the character of the future composer, who was not afraid to react actively to harm, injustice and danger to freedom, including creative freedom. His numerous protests against political decisions provoked various restrictions, including a censorship ban. As a result of these political actions Mycielski’s name would disappear from scholarly and popular publications, and his musical works would be removed from concert programmes.

The musical language of Mycielski’s symphonic pieces was initially marked by expressive neoclassicism (Lamento di Tristano), clearly anchored in the style of Karol Szymanowski. We can hear in Lamento… the aura of Stabat Mater, the ballet Harnasie (or perhaps, more broadly, atmosphere of highlanders’ folklore), colouring use of the piano (like in the second movement of Symphony No. 4, “Symphonie concertante”) as well as a particular predilection for using imitation and reverse movement in the construction of themes. Mycielski still made use of this stylistic idiom after the war, in his Symphony No. 1, abandoning romanticising neoclassicism in favour of accentuation of distant references to the Polish musical folklore. Another purely neoclassical work in his catalogue is Silesian Overture, clearly drawing on Igor Stravinsky’s composing technique (references to Petrushka are evident).

They provide a foretaste of a group of works in which the composer, limiting the means used to a minimum, achieved extraordinary, profound expression. This intuition was confirmed by Stefania Łobaczewska, who commented: “Above all, he is looking for musical expression, concentration, mood and this is where he achieves interesting results, often of very personal nature” (Stefania Łobaczewska, “Współczesna muzyka polska na koncertach krakowskich”, Dziennik Polski, 7 February 1947).

Music critics would always take note of performances of Zygmunt Mycielski’s symphonies during concerts at the Warsaw Autumn International Festivals of Contemporary Music (1962, 1972, 1980). Many stressed, as Dorota Szwarcman has noted, their differentness, and the performers “after their initial resistance [...] completely changed their attitude to the piece, when at some point in the rehearsals the right ‘key’ was found” (cf. Dorota Szwarcman, “Symfonika Zygmunta Mycielskiego”, in Melos – Logos – Etos. Materiały sympozjum poświęconego twórczości Floriana Dąbrowskiego, Stefana Kisielewskiego, Zygmunta Mycielskiego, ed. Krystyna Tarnawska-Kaczorowska, Musicological Section, Polish Composers’ Union, Warsaw 1987, p. 105). With Symphony No. 2 Mycielski began to use his own individual technique of composing by means of twelve notes. Derived from Herbert Eimert’s proposal, the table system became the basis of his compositional technique (cf. Iwona Lindstedt, Dodekafonia i serializm w twórczosci kompozytorów polskich XX wieku, Polihymnia, Lublin 2001), proving so universal for him, that he used it to construct both instrumental, including symphonic, music and works with literary texts, entangled in the sphere of semantics. Mycielski’s symphonic works are characterised by the breaking of the musical matter into small motifs, the interplay, mutual penetration, dialogue and complementation of which build the expressive meaning of the whole. This expression, as has been observed with regard to Symphonic Sketches, written fifteen years before Symphony No. 2, is “restrained, administered in small doses and slowly graded, tentatively uttered [...]. It is accompanied by sound that is slightly raw, far from any external orchestral virtuosity” (Maciej Negrey, “Postacie symfonizmu w twórczości Floriana Dąbrowskiego, Stefana Kisielewskiego i Zygmunta Mycielskiego”, in Melos – Logos – Etos…, pp. 85–86).