The Mycielskis of Wiśniowa

Zygmunt Mycielski’s life can, in fact, be described by these very words:

I am a typical family product, with the notion of family being the one that has remained in Europe since ancient times, through the long centuries of Christianity since the Middle Ages. The notion of family was shared by the peasants, the nobility and the aristocracy. It was closely linked to the notion of a home, seat or the so-called “hearth”. It was a notion stronger than any individual whims and tastes of a given family member (Z. Mycielski, „Pamiętnik", manuscript, Z. Mycielski Archive, National Library).

As we read in his notes:

During my childhood, a child would be described as having the nose of the starost of Konin, the distraction of great-grandmother Alfonsyna, the short-sightedness of uncle Jerzy, the historical interests of uncle Staś or the ornithological passion of the Wodzickis or Dzieduszyckis. All this was classified spot-on, compared to portraits and preserved in oral tradition, like objects collected in houses, pieces of furniture, china, silver, books, paintings and hundreds of knick-knacks each of which had its own story and ceased to be private property to become a historical family deposit. Even jewels were not altered or adapted to the fashion of the day, because every string of pearls, every ruby or emerald was from somewhere, from someone, was a wedding gift or an heirloom depicted in the portrait of great-grandmother Karolina or in the engraving of treasurer Moszyński (ibid.).

As Zygmunt Mycielski stresses:

The Home – the Hearth was so something so overpowering that it meant more than the name. The Potockis were from Krzeszowice, Łańcut, Antoniny or Rymanów – the names of these localities were something that defined the affiliation of a given family member. This was combined with deeply rooted snobbery, both familial and – let me put it this way – “local” (ibid.)

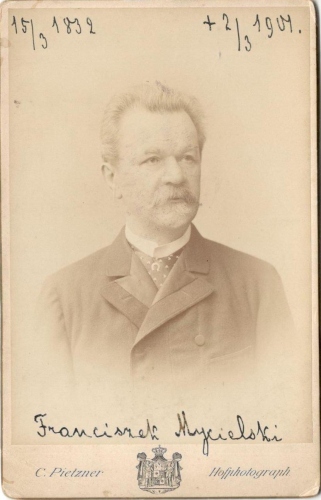

The hearth of the Mycielskis – the branch from which Zygmunt came – was a small village of Wiśniowa in the Podkarpacie region. The modest but picturesque manor was bought in 1867 by Franciszek Mycielski (1832–1901), the composer’s grandfather, who came from Wielkopolska and married Waleria Tarnowska (1830–1914), a representative of one of the best Galician families.

“Wiśniowa cultivated Polish hospitality and European culture,” noted a friend of the family, Stanisław Koźmian (S. Koźmian, Polska pani z ostatniego okresu. Walerya z hr. Tarnowskich Franciszkowa hr. Mycielska, 1830–1914, Kraków 1916).

He was also a friend of Waleria’s brother, Stanisław Tarnowski, the leader of the Kraków conservatives and rector of the Jagiellonian University. According to Zygmunt Mycielski:

[…] the grandfather’s brother-in-law, Prof. Stanisław Tarnowski, a well-known historian of literature, bossed around the entire university and the conservative party. Guests visiting Wiśniowa at the time included, in addition to Stanisław Tarnowski, the two Morawski brothers, Stanisław Koźmian, and the historian Karol Potkański – this was the so-called “alliance of counts and university professors”, which at the turn of the twentieth century was responsible for a beautiful period of “Kraków culture”, with the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences at the forefront and the enfant terrible Stanisław Wyspiański at the back. These were the times of the emerging “Young Poland”, from which my father’s family dissociated themselves, this was the time of Przybyszewski and Boy’s “Green Balloon”, but discussions in Wiśniowa were more about the causes of the fall of the 1830 and 1863 uprisings, Musset’s comedies were put on during my grandmother’s youth, Schumann’s songs and duets were sung, and there were constant talks, with shouting and temperament, about national, political, agricultural affairs, about animal husbandry and horse racing (Z. Mycielski, "Pamiętnik").

Elsewhere Mycielski added: “The Kraków school of history was my kindergarten” (A. Biernacki, “List wnuka (Zygmunt Mycielski o Il Conde Conrada)”, Teksty Drugie 1990 no. 3)

The composer’s grandmother, Waleria Mycielska, liked to surround herself with people from the world of literature, art and theatre. Her interests passed to her firstborn son, Jerzy Mycielski (1856–1928), who became a distinguished art historian, professor of the Jagiellonian University, as well as eminent patron and collector of art works, most of which he donated to the Wawel Castle.

In November 1898 he married Maria Szembek (1877–1951) in Kraków. The young Mrs Mycielska fitted in perfectly with the domestic traditions established in Wiśniowa by Waleria. She, too, was interested in literature, art and music. Her friends included Tadeusz Stryjeński, Józef Mehoffer and Jacek Malczewski. She knew Joseph Conrad Korzeniowski, who was a friend of her father, Zygmunt Szembek (1844–1907). He was the man portrayed by Conrad in his story Il Conde (J. Conrad, Il Conde, 1908. See also A.jBiernacki, “List wnuka (Zygmunt Mycielski o Il Conde Conrada)”, Teksty Drugie 1990 no. 3). Szembek was a restless soul. He played the piano beautifully and had no talent for business. The family considered him to be a wastrel, whose main occupation was wasting the fortune of his wife, Klementyna née Dzieduszycka (1855–1929), one of the four daughters of count Włodzimierz Dzieduszycki (1825–1899), founder of the famous Natural History Museum in Lviv.

He moved there soon after his marriage, accepting the position of steward of the Lubomirskis’ Przeworsk Fee Tail. In 1899 the couple’s first son, Franciszek, was born, followed two years later by Jan Zygmunt, in 1904 by Kazimierz and in 1907 by Zygmunt. All were born in Przeworsk, for a decision was made that after the death of the head of the Mycielski family the widow, Waleria, would be assisted in the management of the Wiśniowa estate by her unmarried elder daughter, Cecylia. As a result Jan could continue managing huge landed estates. He inherited his father’s talent in this domain and was very successful in the field. He was active in the Galician Agricultural Society and the Committee of the Agricultural Society in Kraków. The Lubomirski feel tail flourished under his management. In addition, the young couple enjoyed a happy family life. In 1907 they were expecting their fourth child. The mother sincerely hoped that this time it would be a daughter. However, this was not to be the case and on 17 August they welcomed their fourth son, who was named Zygmunt during a baptism ceremony that took place on 4 September in Przeworsk.

The Mycielskis spent the following few years in Zarzecze near Jarosław and in 1912 moved to Poturzyca near Sokal. In 1914 they decided to settle in Wiśniowa for good. However, as they were travelling to the family estate, they saw mobilisation posters in Lviv – the Great War was about to begin. Therefore, they did not stay long in Podkarpacie. As early as on 17 August they set off for Hungary, only to eventually end up in Vienna. They spent there the following few months and in the summer of 1915 returned to Wiśniowa for good. As Zygmunt recalled: “[W]hen in 1915 the Russian troops withdrew from Kraków beyond the San River, we simply returned via Kraków to Wiśniowa”. And then he noted:

I remember this return very well. My child’s imagination was fired by stories from the frontline. The garden was cut through by trenches, the house was empty, full of bullet holes, with no windows and no doors. The furnishings, partly dismantled by the servants and peasants, were slowly returned to their old place. Hidden silver and paintings were discovered, furniture was slowly being restored. My father was rebuilding the damaged estate, life was slowly coming back to what it was before (Z. Mycielski, "Pamiętnik").

And despite the fact that the hostilities continued and that the changes associated with Poland’s regained independence were embraced with joy, “life in Wiśniowa seemingly went along the lines of ‘the whole world can take up arms, provided Poland’s countryside remains at peace with no alarm’” (Z. Mycielski, Pamiętnik). The parents were busy rebuilding the estate, while the elder sons were soon sent to a gymnasium in Lviv. Young Zygmunt was for the moment taught at home, under the tender eye of his mother.