- Writer

- Introduction

- Publications

A characteristic trait of Mycielski was fullness, multiplicity of matters tackled, constant reflection, integrity and greatness devoid of loftiness. The inquisitiveness of a realist writer and the subtlety of a religious thinker. There is nothing lacking in Mycielski’s oeuvre, no area gains the upper hand, there is a sky-high flight among ideas and a muddy ground underfoot. There is life alongside art, religion, literature alongside music, politics and history, sketches for a self-portrait composed over time, like in Rembrandt’s paintings, and images of others. There is intellectual life and ordinary everyday reality, Europe and Poland. There are constant struggles with himself, with his own body and mind. It would be difficult to point to another individual (perhaps with the exception of Józef Czapski), who lived their spiritual life on a similar level and provided written evidence on a scale of inquiry similar to that of Mycielski. As we read his writings, we have the impression we are looking at Mycielski from close up, listening to his musings, seeing others through his eyes. Sometimes we even feel embarrassed, because he reveals so much to us, he speaks directly to us.

It is hard to set oneself free from Mycielski. From his hypnotic power, freedom and wisdom. It is possible to create his portrait out of fragments of thoughts present in his writings as well as those remembered by his friends.

In Mycielski’s writing there is both decisiveness and uncertainty, a desire to show, as in the case of Montaigne, who one is in the smallest dimension, in every field of action, but in such a way as not to impose oneself on others, with an awareness of the burden one must carry through life. There is in these constantly repeated exercises a testimony to spiritual freedom, inquisitiveness and the belief that one cannot allow, that it is not worth allowing curiosity to fade in us. In his writings Mycielski tells us that we know nothing, ever, for sure. That is why instead of a proud exclamation mark, it is god to put a shaky question mark.

Like Zygmunt Krasiński, Mycielski was convinced that sometimes a stream of beauty was flowing through him, but that he himself was not beauty. That he was lacking something important, that there was a flaw, a difference in him, something that prevented him from focusing exclusively on himself, believing in his own talent, caring for himself. Instead, he preferred to help others, to share what he had been given. He gave away what he had and even what he lacked. He also gave his time. And perhaps even more – his heart and his mind. Because others seemed more important to him, because he valued friendship particularly highly.

Whenever there was a need to speak, to stand up to the authorities, Mycielski did not hesitate. He had the courage to express his opposition, to say “no” aloud, as he did after the attack on Czechoslovakia. He knew that at best he condemned himself to alienation, that his music would suffer. And yet he was in no doubt that he was doing the right thing.

Probably no one else wrote as openly and, above all, as wisely as he did about his erotic life, about moments of happiness and moments of anguish. Without looking for support in psychological musings. Very few people loved and were terrified by Poland like he did. “It’s easier,” he wrote, “to make a ‘revolution’ than a state”. He was unable and unwilling to be elsewhere, and yet he thought about life in Poland exceptionally harshly, painfully to himself and others, because, it would seem, so many things irritated him here, seemed a sign of generations-old intellectual laziness and plain wickedness. “Staś Prószyński,” he noted “was right when he said that if Warsaw used to be a Paris of the North, then now it is not even a Radom of Europe”. And elsewhere: “A foreigner who knew pre-war Poland very well told me in the Bristol Hotel that Poland without Jews, the nobility and whores made no sense”. Mycielski knew, perhaps better than anyone else, that within every nation there were innumerable variants of collective existence and their realisation depended solely on coincidence. He repeatedly said: “In some circumstances the Swiss could be turned into a horde murdering the rest of the world”.

Sometimes he chose silence, proud loneliness, although he sensed that if he had completely abandoned the obligations that weighed him down, he would have “fallen under the surface of life and died noiselessly”.

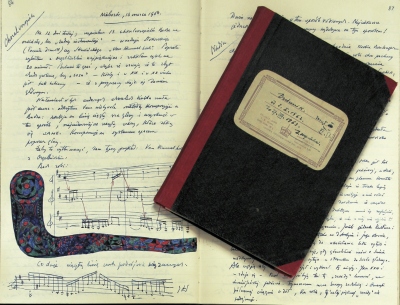

In order to understand Mycielski, it is worth reading his diary, because it provides the most complete reflection of himself and the world, which he always sees sharply, in detail, wisely, to make it visible to others. “The quality of the writing is of prime importance here,” Bohdan Pociej observed, “the gift of an engaging narrative, the ability to hold the reader in the thrall of curiosity. This diary (similarly to the diary kept by Gombrowicz, whose ‘egocentric’ attitude was actually quite alien to Mycielski) excites, fascinates, absorbs, provides food for thought, is hard to put down [...]. This is primarily because this diary is superbly written, because its language is so clear and style so apt; and there is absolutely no sense of the author trying to make the language and the style so – this is yet another mark of outstanding writing. Another characteristic of this style is conciseness”.

Four volumes of diaries stretched between two statements by Mycielski, so important to him – the one from 1950: “I will try to note down thoughts and events in a manner as faithful as possible to my thoughts. If this is possible today, of course”, and the sentence closing the last diary with the remark concerning whether Jan Stęszewski would be able to select from it “some fragments – the rest is to be crossed out, thrown out”. Fortunately, no one crossed out anything. Everything remained.

One of these topics was death or, more specifically, dying, at a difficult moment in Polish history. The following words could be his motto: “Wade till the end into this remnant of life and the world you carry within you”. Mycielski’s diaries feature moving descriptions of the deaths of Janusz Radziwiłł, Jan Tarnowski and the basically posthumous story of János Esterházy (as well as efforts of his sister, a modern-day Antigone). There are pages written with complete honesty, in a moment of reflection on the author’s own fate, written always with dignity, full of emotions, although delivered with surgical coldness and precision. Mycielski records in his diary the death of Maria Czapska and the last days in the life of his friend Henryk Krzeczkowski.

To all intents and purposes, writes Mycielski, I’m now interested only in two things: my own music and death. Death, meaning faith or lack thereof. And when it comes to faith, whether true faith exists.

Every time the death of someone close to him is the end of a world for Mycielski. But before death comes, there beings a withdrawal, a slow departure, giving up of plans. Before a human being disappears from the world, they should account for – to themselves, others and in some cases also God – their own talents. Mycielski sometimes writes about himself with severity, but always calmly, without resignation, without wringing his hands.

What can emerge out of a bubbling of a multitude of (musical!) ideas, designs, patterns in the mind? Is this rich or poor? – there is a similar process with the harmonisation of thoughts with words, with expression of thoughts [...]. It is similar with telling a scene, a conversation, an event, an experience. But in music the material is different [...]. To implement a melodic idea in words, to perform words in music... Ah, yes. Search, hard; don’t search, discover – what can only be EXTRACTED. Emphasise, as simply as possible. Concentration is needed for that, perhaps like the concentration of mathematical thought or perhaps completely different? Too much, too fast, too late; a brief ALWAYS... To turn a mood of panic into calm concentration. Calm and intense to the maximum.

There is also a constant struggle with Poland, with the world, a struggle stemming from both curiosity and independence of judgement. There are reflections on Polish Catholicism that originated on the occasion of Paweł Hertz’s baptism, reflections immediately followed by records of everyday life. For Mycielski’s work is also a unique novel of manners with a vision of communist Poland in the background, a bustle, a fight to maintain dignity on a daily basis among the nuisances of ordinary life. An in addition we get a reminder of the world of the past, distant, gradually erased from our memory, reduced to a few objects with the power to evoke Atlantis. And there is a belief in music, if not his own, then that composed by others, music of the world ensuring spiritual life.

Sadness - writes Mycielski - should be transformed into poetry. It doesn’t work at all the other way round, although most experience it. Those incapable of poetry are sad and they don’t know what it is, they don’t know why they are sad, disappointed, finally helpless. Music is an outlet. For the few. And so is religion. To explain one’s own and thus human catastrophe. Fate. Defence against despair – source of our thinking, our feeling, our creativity.

Some of Mycielski’s sketches will one day find their way into an anthology of Polish essays. These are pieces that help us to think, siding with life seriously, without embellishments and dissembling, without any allowances, written as simply and as beautifully as possible. We need to keep coming back to them. To try to remember them, because, in addition to music, they refer to the entirety of spiritual life or perhaps life in general.

The West is a land where “oranges are cheap”, it is a place we yearn for, we long for, we envy. Seemingly, we are at home there, though usually we come for a brief stay, only as guests. The West is “there”, “here” is our homeland. And one needs to come back from there. But to what? “I will soon return from a country where oranges are cheap,” writes Mycielski,

to a country where, instead of lemons, hawthorn ripens, nipped by frost in the winter. I hurry there, worried that something might have happened there and I have missed it. I hurry to a home I don’t have. I hurry to feelings I am ashamed to reveal. To everything that is too late or too early. To an impression that I’m needed, even if no one needs me.

There is sadness of loneliness and bitterness of recognition in this piece. The courage of a merciless view on who we really are and what is our place on earth in the individual dimension and the dimension of belonging to a bigger community, to a state and a nation. It is a different, brutal version of a confession of love, a modern “Do you know the land”.

Even in Mycielski’s musical pieces written in connection with a particular work, like in the case of Bolero, we can find a parable of almost allegorical nature, about what is simple and what is complex, about how to give thoughts their proper form.

Ravel thought he had written something exceptionally complicated, something the repeatability and mathematical precision of which would be accessible only to musicians, who were the only ones capable of judging it. The belief was probably reinforced by the effort he put into composing both sixteen-bar sections of the theme. [...] However, despite this artificially tightened and stretched length, a few months later the theme did indeed make its way, if not into ordinary people’s homes, then certainly into almost all the establishments and cafés of Paris, although usually no one sang more than the first eight-bar fragment. [...] To want as little as possible and make this little perfect, these were the recipes which Ravel gave his listeners, which he preached and illustrated with examples, when he spoke to the young. We have enough greatness, he used to say. It crushes us, throws us off balance, off all measure, the human measure, which should be our only measure. Only this human measure was his method, slogan and aspiration. No more, no less. To enjoy what is really available to us, every day, and to make sure it’s done perfectly.

In these words we recognise Mycielski’s ear for the melody of life, for the pure tone of spiritual existence and for what is the most corporeal in humans. And at the same time, there is no incoherence, no posturing, no artificiality, because what counts is the daily difficult struggle for a good note, for every well-structured sentence, for a moment in life truly lived, in joy, ecstasy or in sorrow.

He was able to react keenly to what he found in books, always bringing out the essentials. He had a gift for delighting in both a single line of verse and a multi-layered novel, as long as literature grasped something of life, was a window wide open to the world. He was aware that as an artist he was probably guilty of being focused too much on himself. He kept repeated that his only hope was “to constantly go beyond oneself. To objects, to issues, to ideas”. That is why he preferred those who managed, at least for a moment, to abandoned their own “I” in favour of a singular “you”, not to mention those few who moved successfully among issues reserved for the plural. He liked to repeat after Czapski that “art is taking off your trousers in public. Those who won’t do that, won’t achieve anything”. Yet he himself preferred to meet other people’s thoughts. He wanted to maintain a clear vision of things, not hampered by an ambition game, a desire for honours. Critical about himself, he looked only for “good sides” in others. He was happy when he could take something from them, learn something. And yet those same people were a nuisance for him, they pecked him to pieces every day, with everyone wanting something, stealing his time and attention.

I feel - wrote Mycielski - the real bottom in people, unexpressed, I feel what they are, where they are alone, when they think and feel alone. And in artists I immediately see their bottom – revealed by what they do, what they gave, I also often see what they were uncapable of giving [...]. For people art is a lie and life the truth. For me it’s the other way round.

Shortly before his death Zygmunt Mycielski noted down:

there are various measures of the value of human beings: what they did, achieved, or what they were able to do to others (their neighbours! loved ones!), or what they are internally as well as externally – what they are in the eyes of others? What is the ‘value’ of a human being anyway? How much merit, fault, chance is there in it – by birth, by ability, by operation of what is given to us by nature, by the milieu from which I come? So what if I am Polish, was born among the so-called landed gentry, had parents who were wise in life and a big house – and I have moved so far away from that milieu. Whence comes this entanglement in the musical world, whence come the disorder and laziness, devotion and avoidance of effort, carelessness? Whence come the passions, unrealised possibilities, genuine misdemeanours? Resignation, effort? [...] Leaving this world, I cannot not think about what is and about what is not there. Locked in my personality, I stand before an unimaginable nothingness. Without fear, but in loneliness with regard to everything.

This is what he wrote about, profoundly and with talent, never to show off, always for those who wanted to hear the truth. He was not a professional writer, he looked for a place for himself in culture elsewhere. However, his books cannot be passed over; they are part of what is the most important in Polish literature.

MAREK ZAGAŃCZYK