![Pamiętnik [Memoir]](/upload/thumb/2022/11/pamietnik_okladka_auto_400x500.jpg)

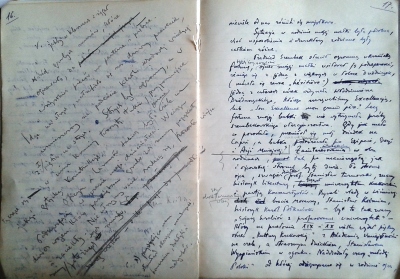

Pamiętnik [Memoir]

ZYGMUNT MYCIELSKI, Pamiętnik [Memoir], manuscript, Zygmunt Mycielski Archive, National Library, No. III 14360.

Preserved in Zygmunt Mycielski’s archives, Pamiętnik [Memoir] is not dated, but seems to have been written in the early 1950s at the latest. Michał Klubiński, author of the Zygmunt Mycielski Archive catalogue, dates it to 1945–1950 (Katalog Rękopisów Biblioteki Narodowej, vol. 24, Archiwum Zygmunta Mycielskiego, ed. Michał Klubiński, National Library, Warsaw 2017). The surviving documents suggest that the composer wrote Memoir with its publication in mind. He abandoned the work, however, realising that publication in the form intended by him would not be possible. This is evidenced by two documents attached to the Memoir. The first is a written opinion addressed to Stefan Żółkiewski, in 1954–1956 head of the culture department of the Central Committee of the Polish United Workers’ Party. Its author (illegible surname) formulates a number of accusations against Mycielski’s Memoir, especially with regard to descriptions relating to the First World War. The second document is a record of Mycielski’s short response to an opinion by a “party colleague”, in which he states unequivocally that “it’s not worth writing a memoir”. Below are the contents of both documents.

I think that a memoir that will pass to the archives of the National Library and that is written by an outstanding individual can be, as a document, completely uncritical.

But if it is to be published, it must give the truth. That is, it can give an idea of the origins of the war, an idea that is erroneous but characteristic of the author in his childhood. Only an adult memoir writer should critically assess his own authentic judgements from his childhood. This is demanded by social morality. All the more so given that your historical judgement will be supported by the great authority of your name – a leading creator and activist of art. A good memoir is apparently a literary genre dedicated to personal experiences. The origins of a war is a scholarly problem. It if is introduced into a memoir, it must be bound by the rules of a historical treatise. Thus memoirs can and should be written. The conditions proposed by that comrade would have raised the value, if it had been preserved.

[illegible signature]

I once began writing a memoir – having reached 1914, I wrote about what I heard about the origins of this war as a child and what I thought about it myself – and what I think.

When I sent it to a friend who was a party member – he lashed out against me for presenting the matter falsely. That the origins were different etc.

Can we write about 1914–18 only from “true” perspectives? But then why write at all? (I wrote what I thought about it, heard about it and think about it). I can read about the Marxist origins of this in an “official” study – therefore, it is not worth writing a memoir!

ZMycielski

![Bogowie [Gods]](/upload/thumb/2022/11/trzy-sztuki_tytul_auto_400x500.jpg)

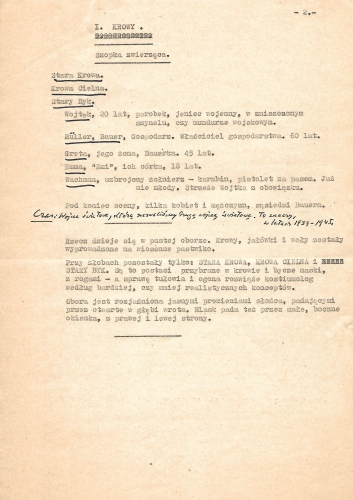

Bogowie [Gods]

In December 1959 the literary journal Dialog published a play by Zygmunt Mycielski entitled Bogowie [Gods]. It is a kind of satirical show in which the author presents the world of the gods in a rather irreverent manner. The characters of God the Father, Son of God and whole host of angels (among whom the Old Angel is an “old fart” and Archangel Michael an “obtuse mercenary”) are full of vices. They are more preoccupied with scheming rather than with matters of humanity. Mycielski added the following note to the published text of the play:

I do not wish this play to be performed on stage in our country. I realise that it would hurt the religious feelings of people who are far from scepticism and from dispassionate examination of the fate of gods and people on earth. Worse things were written about similar topics already in the eighteenth century. Has there been a huge change in this regard in comparison with those days? The situation is different in every corner of the world. Religious, patriotic and national sentiments, to name just those three, are in our case as hot as local sentiments – of belonging to a community or a family. The destruction of such an attachment is improper given the human sensibility, to say the least. Let everyone deal with it on their own. I do not want to play dumb and claim that my Gods is an innocent word play about enshrined dogmas and beliefs. Yet I do not think that the play is an example of mockery and desecration. Gods or God live in human hearts irrespective of any specific images. My little play is not against Gods, but against this void created by people on earth without them.

![Ucieczki z pięciolinii [Escapes from the Stave]](/upload/thumb/2022/11/ucieczki_auto_400x500.jpeg)

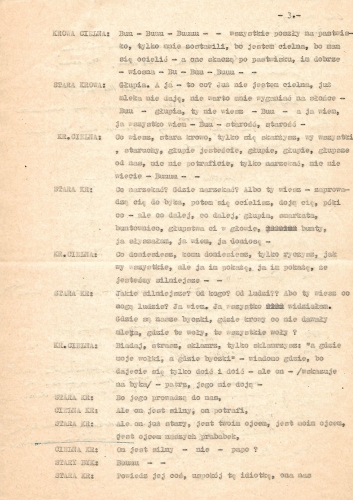

Ucieczki z pięciolinii [Escapes from the Stave]

The book is a collection of Zygmunt Mycielski’s writings published before and in the first few years after the Second World War. It opens with literary pieces – stories published by the young author in the Polish press as well as two post-war stories. Next comes a selection of Mycielski’s reviews and music-related articles as well as speeches delivered during the Polish Composers’ Union or the Culture Council events. They are complemented by journalistic pieces dealing with important social topics (Kielce pogrom, Skiwski’s case). Ucieczki z pięciolinii [Escapes from the Stave] provides an insight into the beginnings of Zygmunt Mycielski’s activity as a writer, going back to the 1930s. In addition, it provides a mirror reflection of the world of Polish music of the first post-war decade, with its ambitions and problems, foremost among them being the increasing political indoctrination. With his contributions Mycielski often responds to the requirements of the day, looking for solutions beneficial to the development of culture. In doing so, he always upholds the artistic value of music.

By including in this volume a number of short stories and contributions that go beyond the field of music, I want to emphasise that the music critic and reviewer should not narrow his or her horizons to just technical issues relating to this art. Let the readers judge for themselves what I thought was needed, necessary or possible and permissible to be said during this period (“From the author”, p. 7).

![Notatki o muzyce i muzykach [Notes on Music and Musicians]](/upload/thumb/2022/11/notatki-o-muzyce_auto_400x500.jpg)

Notatki o muzyce i muzykach [Notes on Music and Musicians]

I am not publishing my feature articles on music from 1955–58. What is included in this volume are just loosely connected excerpts, a selection of what I wrote in that period, especially for Przegląd Kulturalny”.

This is how Zygmunt Mycielski began his introduction to the book. However, as it turned out years later, the author intended it to be a selection of feature articles published by him in Przegląd Kulturalny during the political thaw period, but censors intervened and prevented the book from being published as originally intended. Notatki o muzyce i muzykach [Notes on Music and Musicians] is a compromise, a collection of Mycielski’s notes, the complete version of which was published in 2022 under the originally planned title Znaki zapytania [Question Marks] - see below.

![Postludia [Postludes]](/upload/thumb/2022/11/postludia_auto_400x500.jpeg)

Postludia [Postludes]

The third and last collection of texts published by Zygmunt Mycielski in the press. It comprises feature articles published in the 1970s in Ruch Muzyczny. The range of music-related topics shows the wealth of matters that were of interest to Mycielski. Sketches about music, a large selection of reviews from the Warsaw Autumn festivals as well as tributes to friends (Tadeusz Szeligowski, Antoni Szałowski, Ksawery Pruszyński) and pieces with memories of important encounters from the past (“Two encounters with Wagner”) make up a volume documenting a later period in Zygmunt Mycielski’s writing about music.

![Szkice i wspomnienia [Sketches and Memoirs]](/upload/thumb/2022/11/szkice-i-wspomnienia_auto_400x500.jpeg)

Szkice i wspomnienia [Sketches and Memoirs]

A collection of Zygmunt Mycielski’s writings selected by Paweł Kądziela. It contains sketches published in other volumes as well as those not included in them, but published by the author in the press. Written in 1936–1983, they provide an overview of Mycielski’s journalistic output from his entire career.

![Niby-dziennik [Quasi-Diary]](/upload/thumb/2022/11/niby-dziennik_auto_400x500.jpg)

Niby-dziennik [Quasi-Diary]

Zygmunt Mycielski wrote diaries throughout his life, but it was only after the war that he wrote them thinking that they might be published one day. He gave some fragments to friends to read, depositing the various notebooks with people he trusted, afraid that the communist government might confiscate them. They were published in four volumes after the composer’s death. Critics believe that Zygmunt Mycielski’s diaries are among the most important diary documents of the twentieth century.

Niby-dziennik [Quasi-Diary] was prepared for publication by Mycielski himself, although the composer forbade it to be published before 1995. The volume covers the period from 2 November 1969 to 14 January 1981.

![Dziennik 1950-1959 [Diary 1950–1959]](/upload/thumb/2022/11/dziennik-1950-59_auto_400x500.jpg)

Dziennik 1950-1959 [Diary 1950–1959]

Zygmunt Mycielski wrote diaries throughout his life, but it was only after the war that he wrote them thinking that they might be published one day. He gave some fragments to friends to read, depositing the various notebooks with people he trusted, afraid that the communist government might confiscate them. They were published in four volumes after the composer’s death. Critics believe that Zygmunt Mycielski’s diaries are among the most important diary documents of the twentieth century.

Dziennik 1950-1959 [Diary 1950-1959] was prepared for publication in its entirety by the composer’s niece, Zofia Mycielska-Golik, on the basis of surviving manuscripts. It contains entries from 10 March 1950 to 23 December 1959, with a break between 21 October 1951 and 25 March 1955, when Mycielski ceased to keep a diary after his mother’s death. The volume bears the following motto:

... when you stop believing people, it is no more worth living

![Dziennik 1960-1969 [Diary 1960–1969]](/upload/thumb/2022/11/dziennik-1960-69_auto_400x500.jpg)

Dziennik 1960-1969 [Diary 1960–1969]

Zygmunt Mycielski wrote diaries throughout his life, but it was only after the war that he wrote them thinking that they might be published one day. He gave some fragments to friends to read, depositing the various notebooks with people he trusted, afraid that the communist government might confiscate them. They were published in four volumes after the composer’s death. Critics believe that Zygmunt Mycielski’s diaries are among the most important diary documents of the twentieth century.

Dziennik 1960–1969 [Diary 1960-1969] contains entries from January 1960 to 1 November 1969 as well as a note entitled “10 years later” from 31 July 1978. The author gave it the following motto:

To subject one’s experience to thinking

![Niby-dziennik ostatni 1980-1987 [Last Quasi-Diary 1980–1987]](/upload/thumb/2022/11/niby-dziennik-ostatni_auto_400x500.jpg)

Niby-dziennik ostatni 1980-1987 [Last Quasi-Diary 1980–1987]

Zygmunt Mycielski wrote diaries throughout his life, but it was only after the war that he wrote them thinking that they might be published one day. He gave some fragments to friends to read, depositing the various notebooks with people he trusted, afraid that the communist government might confiscate them. They were published in four volumes after the composer’s death. Critics believe that Zygmunt Mycielski’s diaries are among the most important diary documents of the twentieth century.

Niby-dziennik ostatni 1980-1987 [Last Quasi-Diary] is the most extensive of the four volumes of Zygmunt Mycielski’s diaries. It comprises entries from 16 January 1981 to 15 May 1987. As Wiesław Uchański, CEO of Wydawnictwo Iskry and publisher of all volumes of Zygmunt Mycielski’s diaries, said:

[T]he last volume of the diaries [provides] an excellent closure of the entirety of Mycielski’s notes – also in the existential sense, for it is, in a purely human dimension, a record of Mycielski’s passing, a diary of passing („Mycielski. Szlachectwo zobowiązuje", Kraków 2018)

![Znaki zapytania [Question Marks]](/upload/thumb/2022/11/znaki_auto_400x500.jpeg)

Znaki zapytania [Question Marks]

A new, complete and original edition of Notatki o muzyce i muzykach [Notes on Music and Musicians], published in 1961. Prepared for publication by the author and the publisher, the book was initially stopped by the censors. The typescript has been preserved in the archives of Polskie Wydawnictwo Muzyczne and as a result it has been possible to publish Znaki zapytania [Question Marks] in its original form. A comparison of the two versions reveals the scale of the cuts and changes made in the past. Znaki zapytania testifies to an extraordinary opening of Polish culture and musical life after the period of Stalinist isolation. The pieces included in the volume come from 1955–58, a brief period of political thaw which had a huge impact also on musical life in Poland. Mycielski happily records visits of foreign artists, welcomes with hope the founding of the Warsaw Autumn Festival, notes the increased interest in jazz, writes about the cultural achievements of recent years – but also fiercely points out the shortcomings and cases of negligence in the national cultural policy. The whole ends with five Letters from the West written by Mycielski in 1957 during his first trip in years to France and Switzerland.