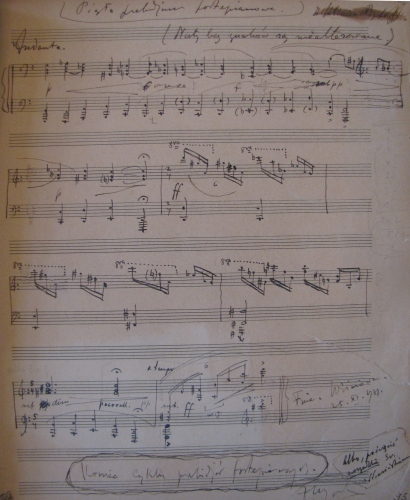

Five Piano Preludes (1931)

dedication: to Sviatoslav Strawinski [à mon ami Sviatoslav Strawinski] (also visible crossed out or blurred earlier dedications of individual preludes: to Zygmunt Przeorski, to Lubomir Pipkoff)

czas trwania: ca 8’

manuscript: Zygmunt Mycielski Archive, Manuscript Department, National Library, no. IV 14313, akc. 020704

premiere: ?

In addition, they were dedicated to different people – for example, the piece written first, in August 1931 in Paris and incorporated into the cycle as Prelude no. 2, was initially called Piano Allegro and was to be dedicated to one of Mycielski’s piano teachers, Zygmunt Przeorski. The chronology of the writing of these miniatures and their original dedications are explained in the table below:

| order of writing | place and time of composition | original dedication | original title |

| Prelude no. 2 | Paris, August 1931 | to Zygmunt Przeorski | Piano Allegro |

| Prelude no. 1 | Wiśniowa, 21/22 October 1931 | crossed out | |

| Prelude no. 3 | Wiśniowa, 5 November 1931 | illegible | |

| Prelude no. 4 | Wiśniowa, 23 November 1931 | to Tadeusz Szeligowski | |

| Prelude no. 5 | Wiśniowa, 25 November 1931 | to Lubomir Pipkow |

In the end, as he noted in Szkice kompozycyjne 1927 [Compositional Sketches 1927], he decided to combine them into a cycle dedicated to Sviatoslav Stravinsky (son of Igor Stravinsky), whom he got to know during Nadia Boulanger’s courses.

This is how Mycielski described the writing process in letters to his mother: “I’m coming back from the last (fifth) prelude. It’s late. [...] I finish the collection with a kind of chorale. It’s lying in front of me, a fresh fair copy, and I’m moved by what has happened” (21 November 1931).

Like in the small cycle of preludes from 1928, he, too, each miniature can be interpreted as a study of a problem. What comes to the fore again is the question of rhythm.

Prelude I dazzles with a thick texture and high dynamic level, octave and two-note passages grouped correspondingly to the changing metre (from 7/8 through 4/4, 3/4/ to 4/4).

The next miniature, Prelude II, unfolds on a lower dynamic level, in a slightly slower tempo. A clearly thinned two-voice texture makes it possible to add variety of the rhythmic layer and consistent use of polyrhythmic devices. The narrative is interrupted twice with a waltz reminiscence (tempo di valse).

The central Prelude III brings a clear agogic contrast. After the relatively fast first two sections the composer almost stops all movement and makes the melodic line more song- mellifluous, having it accompanied initially by a counterpoint gradually transformed into a centralising figure, as it were.

Prelude IV is to some extent announced by the waltz “interventions” in the second part and the centralisation present in the third part of the cycle. In the first section of this “mad waltz” a constantly repeated melodic figure is fashioned into a broad melodic line with an accompaniment in the form of a pendular motif played as if “against” the bar line and triple-metre pulsation.

The cycle ends with a chorale complemented by a coda (Prelude V) developing in the lower piano register and notated without the bar line. The slow, restrained movement of homorhythmic crotchets in a chord texture provides a counterbalance to the earlier polyrhythmic and polymetric solutions.

Writing about the cycle to his mother, Mycielski was pleased with the effect achieved:

I’m strangely moved by the expression of these notes – although, like everything else, these are just a few bars (21 November 1931).

He also informed her that he was planning to compose a cycle of piano etudes. However, nothing came out of these plans.