Liturgia sacra for choir and orchestra (1983–1984)

instrumentation: 3 fl, 3 ob, cor ing, 4 cl B, 4 fg, cfg, 4 cor F, 4 tr, 4 trbn, tb, coro, quintetto d’archi

dedication: –

duration: ca 27’

manuscript: Zygmunt Mycielski Archive, Manuscript Department, National Library, no. IV 14192 akc. 020583

premiere: Warsaw, 26 September 1986 (Warsaw Autumn), State Philharmonic Orchestra and Choir in Kraków, cond. Tadeusz Strugała (chorus master – Stanisław Krawczyński)

Although many of his statements verge on agnosticism, there are recurring motifs in his writings that testify to his attachment, which originated in his family home, to a “spiritual foundation” or his longing for an undefined perfect Being.

Extraordinary importance was attached to a comprehensive upbringing by the Mycielskis, and the thorough education of the children was preceded by the instilling in them of respect for the homeland, centuries-old traditions and customs. Care for the culture of the spirit was manifested in the collection of works of literature and art, the opening of the Wiśniowa manor to frequent visits by artists, and, with regard to the youngest, in the awakening in them of a need to commune with art. In the evenings the mother would read to the children works of Mickiewicz and Sienkiewicz, as well as fragments of the Old and New Testaments. The stories of the creation of the world and expulsion from Paradise became so imprinted on the future composer’s memory that in later years he would toy with the intention of setting the Book of Genesis to music.

Despite such strong foundations Mycielski distanced himself increasingly from the formalised rites of the Catholic Church. During the Second World War, while he was kept in a POW camp, Mycielski, out of a sense of shame or perhaps helplessness, took part as the only one of the three thousand fellow prisoners (one of two fellow prisoners, according to another source) in a clandestine Mass celebrated by a Breton priest, Father Rio. His participation in the Eucharist not only strengthened him spiritually, but also prompted some dramatic observations: “heaven was unfeeling, silent and cold”, “Mass suffering does not bring man closer to God”.

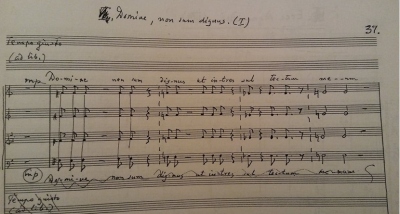

At some point during the writing of the mass, Mycielski shed light on his personal attitude to religion and faith with a brief statement: “God must exist!” (Zygmunt Mycielski, Niby-dziennik ostatni 1981–1987, Iskry, Warsaw 2012, p. 316). This “personal” attitude to religion found its reflection in a “personal” form of Liturgia, with the composer deliberately giving up the classic form of the ordinarium. It was replaced with a paraphrase of the musical mass, its only remaining canonical elements being the texts of the Kyrie, Sanctus and Agnus Dei. Mycielski did not include the Gloria in his cycle and limited the Credo to short selected fragments referring to the Holy Trinity. In addition, he added to this unique compilation fragments that were to be recited: the words describing Christ and spoken by John the Baptist (Ecce Agnus Dei), the prayer preceding the reception of the Eucharist and expressing humility and respect, trust and love (Domine, non sum dignus) as well as the final blessing (Benedicat vos).

Such an untypical form of the mass was somewhat “mitigated” by Mycielski, who anchored it in the traditional stylistic idioms he got to know when studying with Nadia Boulanger. In Liturgia sacra we can hear both quotations from medieval monodic chant and the “hard” chords of fourths and fifths typical of the first polyphonic superimpositions on Gregorian chant; experiments with sound colours characteristic of Josquin; melodic structures in the intervallic form of the B-A-C-H [B flat-A-C-B] musical cryptogram; or the austerity of sound marking Stravinsky’s religious compositions. These elements are made objective, as it were, by Mycielski’s individual idiom, noble, Latin, avoiding nineteenth-century pathos, emphatically revealed in the humble confession “Lord, I am not worthy”. Like the Centurion from Capharnaum, he has the performers sing – with full humility, with no exaltation, almost in silence – the words he wrote about a year earlier: “A few old sentences: ‘but only say the word and my soul shall be healed’, ‘let us proclaim the mystery of faith’, open up new horizons, which transport us to a world different from the one that seems to be” (Zygmunt Mycielski, Niby-dziennik ostatni…, op. cit., p. 180).

The dimension of the composition was interpreted in a unique manner by the composer’s friend Czesław Miłosz, who wrote:

He was able to be here, before me, and at the same time he was in a different land, from which his own ‘Self’ seemed tiny, as if viewed from a reversed telescope. [...] I guessed a metaphysical experience in him, an experience that transported him high up, almost into the dimension of sanctity. Who knows, perhaps that trace has been suggested by his last composition, Liturgia sacra? (Czesław Miłosz, Rok myśliwego, Znak, Kraków 1991, p. 84).