These words shed light on the doubts which – accompanying the composer since his youth – drove him away from the Catholic Church for a while. Despite the fact that Mycielski’s was the attitude of an agnostic, we can often find in his writings a recurring longing for what is perfect, higher than matter.

The first information pointing to his desire to set Psalm XLII to music comes from November 1980: “We have nothing that could replace the psalmist […] Introibo ad altare Dei. Kneel down here” (Zygmunt Mycielski, Niby-dziennik ostatni 1981–1987, ISKRY, Warsaw 1998, p. 218). One year later Mycielski noted in his diary small sketches of the division of the text of the psalm between the voices of the choir and shared the controversy surrounding his creative choices: “So why this desire to write an Introibo, Judica me and ‘Emitte lucem tuam et veritatem tuam’?” (Zygmunt Mycielski, Niby-dziennik ostatni…, op. cit., p. 96). The composer’s later statements, while dispelling the dilemmas that accompanied his pre-compositional work on the Psalms, confirmed the sources of his aesthetic fascination with Old Testament texts:

I still have a lot of humility and wonder before the beauty of archaic texts, among which the Bible and the poetic Gospels are the peak of human beings’ conversation with, quarrel with and humility before God. That is why I have written the Psalms (Zygmunt Mycielski, Niby-dziennik ostatni…, op. cit., p. 623).

Although Mycielski had at his disposal some Polish translations of the Book of Psalms (the essence of Polish spirituality and culture in the form of Jakub Wujek’s sixteenth-century translation from Latin, Jan Kochanowski’s Renaissance paraphrase from 1579 or the Psalms translated from Hebrew by Czesław Miłosz), he decided to set to music the Latin texts from the Vulgate. The composer may have been helped in selecting the psalms by Father Jan Twardowski; in addition, we can point to Czesław Miłosz and Stanisław Kołodziejczyk as persons with whom Mycielski consulted about any emerging doubts of linguistic nature. In an auxiliary translation added to the score Mycielski used Wujek’s and Kochanowski’s texts.

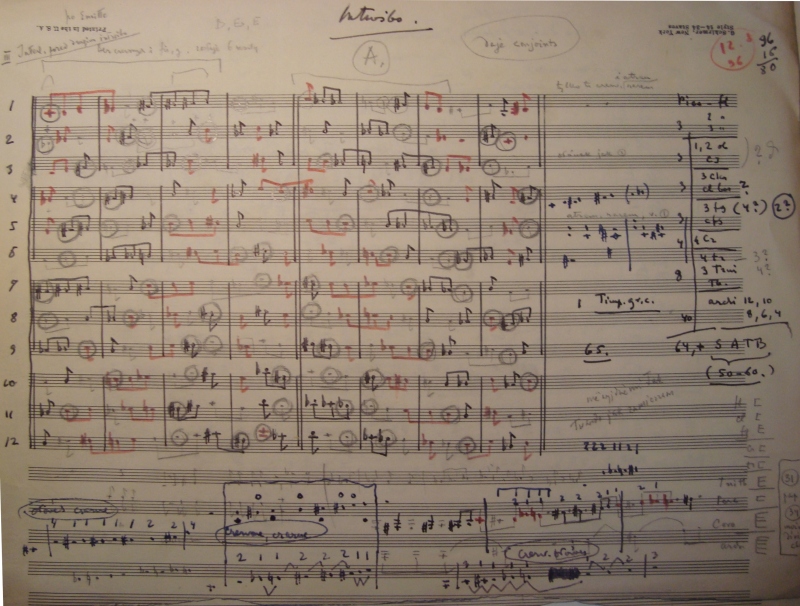

The composer wrote about his Psalms on 9 March 1982: “I will write in a way that will bring out the meaning with music” (Zygmunt Mycielski, Niby-dziennik ostatni…, op. cit., p. 180). The basis of the sound material of the composition is a “row” of twelve notes, strongly highlighting dissonant sequences, especially major sevenths. Another group of note and chord sequences present in the Psalms was described by the composer in the following manner:

[F]ifths, fourths, octaves, fascination with pure intervals. These are some ‘eternal’ sounds. Sounding intuitively (?) in Gregorian chant in what is not yet art but is music (Zygmunt Mycielski, Niby-dziennik ostatni…, op. cit., p. 163).

This is also how the first link of the cycle begins – against a backdrop of a highlighted major seventh followed by a semitone bundle of notes (F sharp, G, G sharp) pure fifth chords resound in the lower register in anticipation of the introduction of the choir, which intones the antiphon Introibo ad altare Dei in unison. The juxtaposition of the musical language of Mycielski’s times with archaising melodeclamation with characteristics similar to those of the opening cadence in psalmodic verse directly brings to light spiritual inspiration in the form of an immanently religious element, harmonised with structures adapted to the requirements of achieving a call full of hope and trust.

The structure of the piece consists of a succession of psalm verses interspersed with an antiphon, the subsequent appearances of which are characterised by a widening of the sonic and dynamic range. The hopeful words “Spera in Deo” [“Have hope in the Lord”], introduced before the final antiphon (b. 122), are lightened up by material of chorale provenance and an accumulation of pefect consonances, the meaning and symbolism of which Mycielski had learned thanks to Nadia Boulanger’s lectures.

Similar musical means can be found in the setting of the remaining parts of the triptych: the primacy of the text, its clear delivery, bringing out a dramatic element from it (sometimes with a division into dramatis personae), naturalness of the rhythmic outline and assigning to the psalms excerpts appropriate “positive” and “negative” figures – all of them testify to an in-depth interpretation of the message of the three fragments of the Psalter.

It is music of prayerful concentration achieved by means of simplifications and reductions, expecting seriousness and concentration from both the performer and the listener…