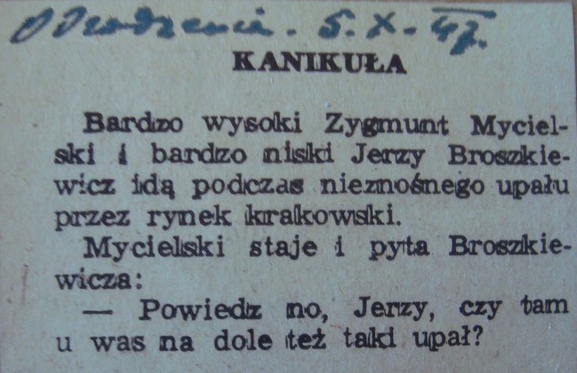

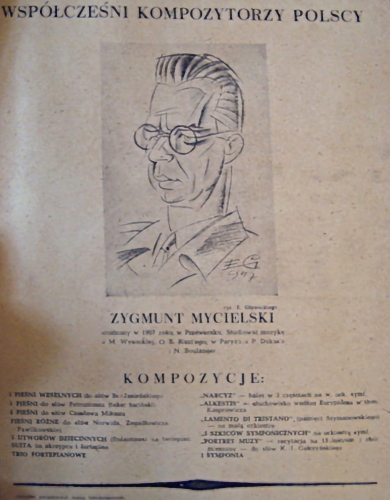

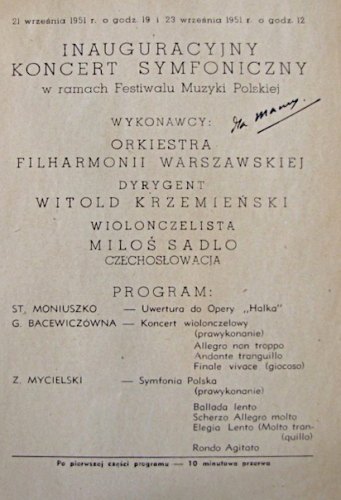

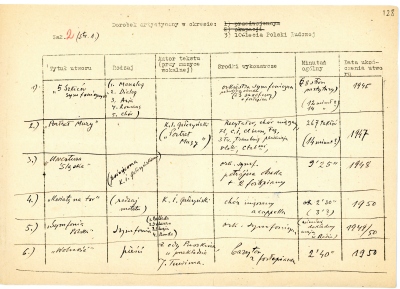

He had known many of them since before the war. Now, the predominant feeling among the many whirling within him was joy. He was coming back to his own people. Initially, he moved in with his mother in Kraków, but after a while he moved to Warsaw. Soon he became actively involved in various spheres of cultural life. As early as in 1945 he became a member of the Publishing Council of Polskie Wydawnictwo Muzyczne - PWM Edition. In 1946 he joined the Polish Composers’ Union and the editorial team of Ruch Muzyczny, a journal on the pages of which he had appeared already in December 1945. His pieces were also published in other journals and newspapers, like Przekrój, Nowiny Literackie, Dziennik Polski, Tygodnik Powszechny, Odrodzenie and even the very leftish Kuźnica. In his writings Mycielski tackled mainly musical themes, although sometimes he would refer to urgent problems of public life as well. He wanted to be actively involved in the shaping of Poland’s musical life. In order to achieve that goal, he did not shy away from talking to both his fellow musicians and the authorities. Both appreciated his balanced views and a desire to seek a consensus for the common cause, that is the quality of Polish culture.