Juvenilia

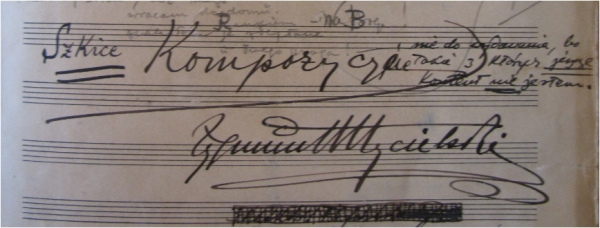

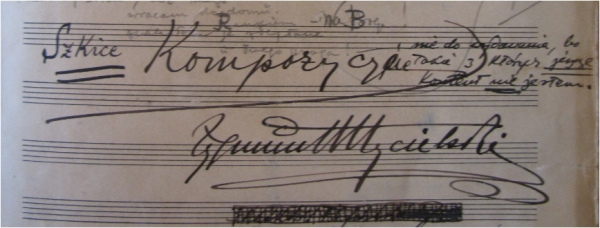

We can get to know Zygmunt Mycielski’s youthful oeuvre by studying a music notebook entitled by the composer Szkice kompozycyjne 1927 [Compositional Sketches 1927] (deposited in the Zygmunt Mycielski Archive at the National Library).

Contrary to the misleading title, the collection does not comprise pre-composition material or pieces composed only in 1927 – it is a compilation of nearly twenty compositions completed between 1927 and 1938, written in Wiśniowa as well as Paris, Kraków, Vilnius and Bukowina Tatrzańska.

| No. | Work title | Place and time of composition |

| 1. | Allegro molto for piano | Wiśniowa 1927 |

| 2. | Śmiech [Laughter] for alto with piano to words by Józef Krzyszkowski | Wiśniowa 1927 |

| 3. | Cztery pory roku [Four Seasons] for soprano and piano to words by Leopold Staff | Wiśniowa 1928 |

| 4. | Triolets for soprano and piano to words by Emil Zegadłowicz | Wiśniowa 1928–1929 |

| 5. | [Two] Preludes for piano | Kraków, Wiśniowa |

| 6. | Mazurka in A minor for piano [homework for Nadia Boulanger] | [Paris] 1930 |

| 7. | Litość [Charity] for soprano and piano to words by Cyprian Kamil Norwid | Paris 1930 |

| 8. | Three Violin Preludes (for violin and piano) | Wiśniowa 1930 |

| 9. | Wiśniowa, Paris 1931 | |

| 10. | Petite piéce pour piano [Triptych for piano] | Wiśniowa 1931–1932 |

| 11. | Gorzka zatoka [Bitter Bay] for soprano and piano to words by Maria Pawlikowska-Jasnorzewska (1932) | Wiśniowa 1932 |

| 12. | Gdzieżeście?! [Where Are You?!] for soprano and piano to words by the composer himself | Wiśniowa 1932 |

| 13. | Piéces pour piano, e’galant de sonorité le violoncelle | [???Wiśniowa] 1933 |

| 14. | [Prelude] Allegretto for piano | Wiśniowa 1933 |

| 15. | Lento for cello and piano [later the third part of Four Preludes for piano and cello] | Vilnius 1934 |

| 16. | Vivo for cello and piano [later the fourth part of Four Preludes for piano and cello] | Vilnius 1934 |

| 17. | Vilnius 1934 | |

| 18. | Stimme eines jungen Bruders for soprano and piano to words by Reiner Maria Rilke | Bukowina Tatrzańska 1938 |

These are, obviously, not all compositions written in 1927–1938 – the collection lacks such popular pieces as Trio for piano, violin and cello as well as Five Wedding Songs to words by Bruno Jasieński from 1934 or Lamento di Tristano, written in 1937, at a time when the news of Karol Szymanowski’s death reached Poland. In addition, there is no trace of Lauda Sion, a piece composed under the guidance of Nadia Boulanger in 1930, or Psalm XXVIII, the composition of which was mentioned by Mycielski in letters to his mother Maria in 1934.

The most important among, visible right next to the title Compositional Sketches, concerns the composer’s harsh self-assessment of the attempts at composition included in the notebook: “not to be published, for I’m not yet content with them”.

There is no doubt that they do not represent a uniform style. The first works, the piano Allegro molto and the song Śmiech, submitted to Szymanowski, are characterised by a hypertrophy of musical ideas. It seems that the nineteen-year-old composition student wanted to present both his pianistic skills and a number of ideas which he was unable at the time to use to develop the musical form. No wonder, then, that Szymanowski immediately said, as he was looking through the score: “You don’t know the form”. The compositions were constructed as an assembly of small musical ideas, which, consequently, led to a lack of a logical, smooth narrative. The fact that the works were chopped into irregular, several-bar segments, almost each of which was based on a dynamic arc with a characteristic build-up, reinforced by a fragmentation of rhythmic values and slight tempo fluctuations, clearly demonstrated an inability to plan the fluctuations of tension and relaxation – afflictions typical of the composer’s youthful personality. The effect was compounded by a constant change of metre, even to metre as untypical as 17/16, as well as neoromantic tonality and harmony. Mycielski often used accidentals, usually opting for “dark” flat keys, expanding them to the full chromatic range. He uses chords with varied morphologies, stressing the selected tonal centre at the beginning of segments, but fairly quickly moving away from it.

Aware he was dealing with still unbridled youthful imagination, Karol Szymanowski recommended that Mycielski study Bach’s fugues and Chopin’s preludes. It seems that the young composition student did his homework conscientiously, for in his next works he gradually made the texture thinner, simplified the chromatic layering, moved towards diatonic orders, making sure above all that the musical form would be clearly shaped. What certainly also contributed to this were his studies under the guidance of Paul Dukas and Nadia Boulanger. Thus some of his later pieces could – as regarded much more highly by Mycielski himself – find their way into lists of his works.